Awardee Spotlight: 2017 Grace Holt Award Recipients

Get to know the 2017 Grace Holt Memorial Awardees: Katie Speth, Taelar Scott, and Ethalle Thompson, in this interview about their lives in and out of college. Hear about their research and their goals moving forward.

Taelar Scott: Psychology and African American Studies major

Why did you choose your major?

Taelar Scott: At first I wanted to be a psychologist, so it made sense to major in psychology. But during my freshman year I took AAST 100, just as a gen ed, and I fell in love with it. I started to learn about my identity in the black community, my history and the legacy my people had left behind. I had heard for so long that black people were only slaves and then MLK came to save the day and our lives were good ever since. And that was a complete lie. African American studies taught me how to be critical and not to take the history I was given as verbatim.

Do you consider yourself an activist?

Scott: I do consider myself an activist. Activist and activism is so diverse. But I do everything in my power to bring about political, emotional, and mental change to the black community. Interning at the Better Boys Foundation and creating a new program to redefine black identity is how I do my work. As well as just knowing black history and the structures and systems put into place to set the black community back. Being awake to all of this is also how I do activism.

Part Two of Interview with Taelar Scott

What is an issue you care about?

Scott: Young black women is an issue I care deeply about. Yes, we are on the rise graduating from colleges but we are also on the rise for HIV infection, STD and pregnancy rates. And the fact that the issues black women face seem to hold no meaning or weight. For example, the black girls who were going missing everyday, but the news was not covering it. It took social media awareness for the news to talk about this issue. Black women’s bodies hold no value and that needs to change. Otherwise, rape, domestic violence, kidnapping, and so forth will always go unrecognized and unpunished.

Katie Speth: African American Studies major

So you were in a different field and decided to move over to African American Studies—why did you do that?

Katie Speth: I think it was a very logical path. I started out in education at UW Madison, dabbled in social work, took a year off and did a lot of volunteering that directed me to where I am now. I came here for criminal justice and from that went to African American studies. Being interdisciplinary I felt I was able to study all of the things I cared about. Not only could I combine all of those things but none of those by themselves I felt was doing justice to what I actually wanted to do. I always wanted to be a teacher, to teach English in an inner city. I come from a different background so I’m already going to be jumping through some hurdles so I wanted to make sure I wasn’t being limited and could develop a better understanding of minority experiences.

Is there a certain research project that means something to you?

Speth: Right now I’m doing my final senior research project on black barbershops. It’s hard because with research in undergrad I can’t interview them. I felt like I couldn’t put my own voice and flare on it because I couldn’t go in there and be a part of it. My point in doing it (my so what?) was that if we could establish barbershops as a place where important dialogue [take place] for educational purposes or community organizing, then those experiences wouldn’t be so ignored.

Part Two of Speth Interview

How did you become interested in it?

Speth: For some reason, I’ve always been interested in them. My great uncle owns one of the oldest barbershops in Chicago, Karl’s Barbershop. He’s this old German guy. The barbershop is such a classic scene with all these old men sitting in there, talking all day, some of them not even there for a haircut. I don’t necessarily think it came from him, but I brought my friend from Germany over there. Watching them interact was a cool cultural dialogue. For black barbershops I think there is an entirely different layer because it’s primarily black people only in the barbershop because you’re going there for your specific hair care. Some of the articles in my study talked about how in general somebody touching your hair is a personal connection but with the added cultural layers of ‘oh i understand how your hair works.’ They also hear history there that they may not hear in their schools.

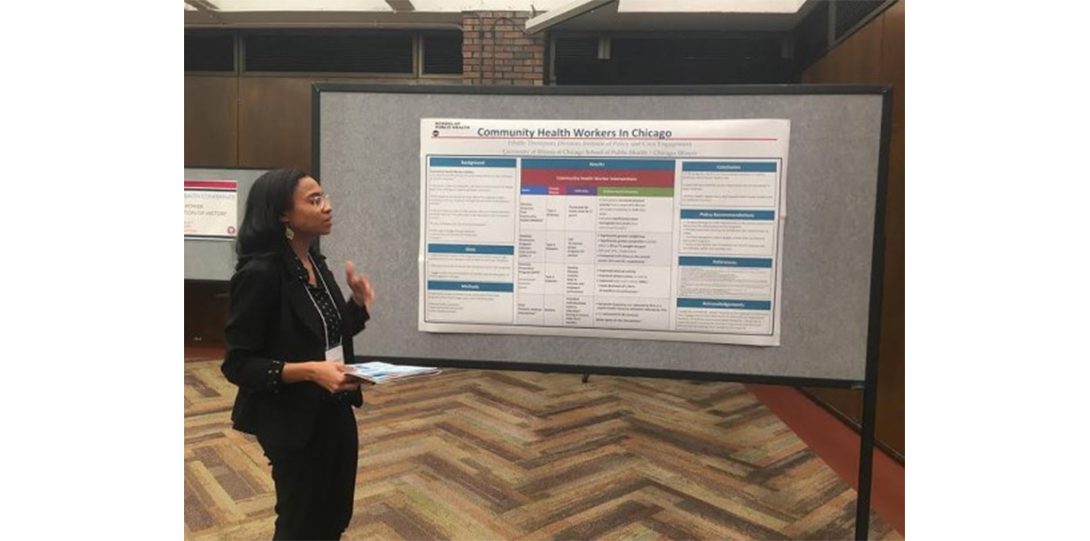

Ethalle Thompson: public health major

What is your major/why did you choose it?

Ethalle Thompson: So my major is public health. Before I was a biology major for three years and I didn’t enjoy it. I felt like I was learning about the body, but I was missing the interaction between the communities that are affected by the same diseases I was learning about. I chose public health because I was really interested in the crossroads of social science and medicine. I wanted to see how disease affected populations especially those without the means to prevent it. Thus, I was introduced to public health which is the study of population health. It’s not focused on individual treatment but on community treatment and most importantly prevention. I have a passion for identifying health injustices and public health allows me to give a voice to vulnerable populations and come up with solutions to these social health problems.

Do you have a particular health injustice that you study/are involved in?

Thompson: I really advocate for minorities who experience much structural and institutional racism through the frame of health. Many Black and Latinos in urban areas have the highest rates of disease because of their limited access to health care especially in cities like Chicago. Unfortunately, in the US health care is not a right, but instead it is a privilege for those who are wealthy enough to afford resources. These vulnerable populations are left without quality health care and are exposed to a lot of health risks because of their lack of access not only to health care but a better quality of life in general. Minority populations in urban areas have the fewest opportunities to healthy foods, higher paying jobs, and education just to name a few injustices. So ultimately, I seek to uncover the reasons behind these injustices and possible solutions to improve the quality of life for minority populations.

Part Two of Ethalle Thompson Interview

What are the possible solutions?

Thompson: One solution to part of this massage issue is to increase the access to health care through something as simple as transportation for community members who have to travel too far for a doctor’s appointment. Another solution within increasing access is using Community Health Workers who have a close understanding of the community. They also educate the community to understand the importance of seeing a primary care doctor and bridging the gap between medicine and minority communities. I also believe a lot of funding is lacking in general for public health and social work. We think the problems can just fix themselves when people fix themselves. However, when there are so many systemic issues that influence the health of minorities, it takes more funding for programs and research to address these issues. There needs to be more understanding of a larger system that is broken to address the needs of these minority populations. Education is a start and that’s one powerful tool to help change systems. I think the moment we think health care is a right is really when we can improve quality of life for minorities in these areas.