Faculty Spotlight: Professor David Stovall

Conducted in Fall 2016, we talked to David Stovall about his book Born Out of Struggle: Critical Race Theory, School Creation and the Politics of Interruption. Professor Stovall shares own experiences teaching and working with students.

Part One of Interview with Dave Stovall Heading link

How would you describe your book to students, what is the rationale, and why did you write about this topic?

Dave Stovall: The book is about researcher responsibility to community driven efforts. So when a group of members in a community have engaged in a larger justice issue they have deemed important to them—if researchers or people from academia or colleges and universities are called in to work with them—then the question that I’m asking is what are the duties and responsibilities of that person? Not from a research perspective as much as it is from a justice perspective. Whatever the community has determined to be the justice condition they are trying to achieve, how do people from research/academic community support those efforts? So that culminated in me working with a group of folks that were demanding educational justice in their community. It manifested itself with me working on the design team and then teaching at the school.

Have you had any students read the book and ask questions about it?

Stovall: I tried to write it in the plainest speak I could so it could be used in undergraduate courses for sure. I have not used it in my own, because it’s a little too pretentious for me, but some friends of mine have used it in their classes. A few folks this past spring and a colleague at Cal State Pomona are using it in their classes.

Was the public sphere an immediate motivation?

Stovall: I think it was broader society, but also in terms of education and research, because in a lot of spaces the initial training is that you’re supposed to have some distance between the communities in which you work for this false notion of objectivity. But I’m with the camp of folks who are trumping that and saying ‘this isn’t about objectivity.’ It’s more so about how are we supported these things communities have termed to be justice conditions—what makes sense to them? It was really me trying to interrupt this idea of being too close to something and saying, well, why aren’t we close?

Do you touch on methodology? Ethnography?

Stovall: Yes.

Is it more philosophical in nature or methodological?

Stovall: I think that I teeter between both because it’s methodological in documenting the process I engaged and it’s theoretical in that it uses a construct to explain my approach for engaging the community like I did. It wasn’t me approaching them like ‘hey can I do work on critical race theory?’ It was more so the community said we know you do educational work. Will you work with us in building, creating this process? My own reflections were looking at this theoretical construct because there was someone before me in the late 90s doing similar work. I thought about his work and the ways in which his work, my work, were latching onto his. This is a guy named Eric Yamamoto, who is a lawyer and a law professor who worked with garment workers in LA to develop a legal clinic to address their concerns with their working conditions. His main premise is that we need to spend less time with abstract theorizing and more time with people on the ground.

In African American Studies, do you think it’s focused a lot on theory?

Stovall: I think in the general sense of African American studies it can be very theoretical, but I would argue that’s a departure from where black studies started. Black studies started as a way for students to claim their humanity and contributions to the world through a discipline that was community-based. That was based on understanding contributions, contradictions and to work on moving forward. In that sense, I feel like I’m trying to continue that tradition of community studies, but there is a trend of people distancing themselves from work that is more on the ground. I would consider my work as a return on doing work that’s on the ground.

I think that theory can improve our work but we have to be intentional about making a connection between the theoretical construct and our work on the ground. There’s a long history of folks that have done this work. But that is unfortunately what a lot of departments will push away from, and this book is a way for me to say here is what it means to go towards making our theoretical contributions make sense on the ground.

You mentioned that the book is an interruption of sorts. Is that something you think about a lot in regards to your work?

Stovall: I try to position myself as someone who is not in concert with traditional conventions. How do we do this work? What informs our work? Based on what we’re trying to do, how do we now engage? Sometimes the rules may assist us and other times they may inhibit us. I’m of the ilk to say let’s see what it means to do things differently, and what are the successes and challenges?

How do you take that philosophy into your teaching?

Stovall: One aspect is learning the rules so you know how to break them and another is that we need to know how the world is in its current moment, but that shouldn’t stop us from thinking about what we can change.

Part Two of Interview Heading link

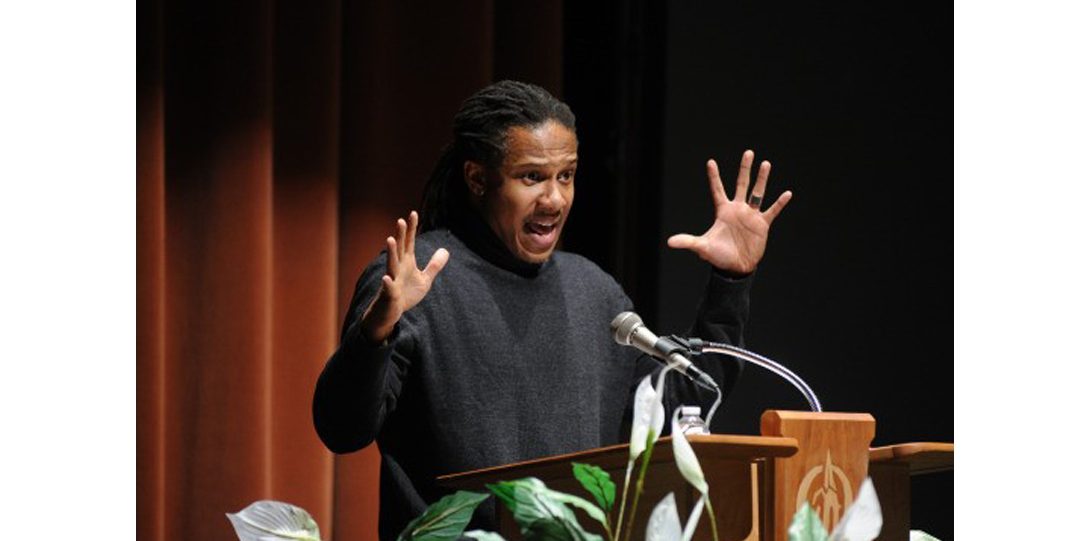

Is the way you speak to an audience at events the same approach you use for teaching students?

Stovall: The way I actually engage folks in day-to-day conversation and in classrooms is pretty much the same. It’s this idea of not placing so much weight on the content of the class but saying what are we dealing with? What are these large and small questions that people are questions and putting their bodies on the line for? And how do we understand that in relationship to what we’re talking about here? I am not as keyed into the conventions of a particular discipline but am really talking about what are folks doing and how can we understand it. So my approach is very conversational in terms of how I am understanding it. I’m literally trying to articulate it as I’m thinking it, so I’m not trying to filter it in a broader sense.

Do students call you Dave or Dr. Stovall?

Stovall: [laughs] And everything in between. It’s a broad range.

Back to teaching content, for African American Studies classes, it seems the courses are just inherently complex and many of the students that take them are doing so because of pure interest, not requirement. Does this leave the construction of class content very open?

Stovall: I think to your earlier point, it’s that open, and I think people in their classes are trying to be reflective of the complexity and layers of black life. A lot of folks who teach here in black studies are trying to interrupt this idea that black folks are a monolith, but to say there are hundreds and millions of people directly connected to the African diaspora and there are so many complexities based on ethnicity, place, language. Everyone is trying to get at a deeper analysis.

Do you try to bridge the gap between African American studies and educational policy studies or is it more helpful to demarcate them?

Stovall: I try to bridge that gap in saying that there are a lot of folks whose work historically is included in some of the black studies literature. Education is added into that paradigm but a lot of times it’s wrongly separated. In my class I try to pair those works.

Which classes are you teaching this semester?

Stovall: Race and Racism in Education, which is a graduate course in critical race theory. I have another class in social theory in educational foundations, which is kind of a subset of policy studies. Both of them graduate classes. I also teach an undergraduate class in the spring—Race, Place and Schooling. The other is a mixed class—Youth Culture Community Organizing in Education.

Do you develop these courses along with the department or are you given these classes and you need to figure out how to utilize them?

Stovall: It’s more developing it with the department, figuring out where the gaps are in the larger curriculum and then what will be my intervention in terms of filling some of those gaps that we may have. And my role is making that connection between African American Studies and Education. It’s often assumed but very rarely explicitly articulated.

Was this something you were able to look at later in your academic career or also earlier in your career?

Stovall: I didn’t actually move over to black studies until 2006. But even in undergrad I started to see that education was kind of on its own island but for all the wrong reasons. There is this k-12 separation for folks in colleges of education. I was always thinking of the pairings. There is a long history of community engagement of black studies departments with k-12 schools, so really was asking this larger questioning and bringing that pairing back as someone who has a degree disciplinarily in education. I wanted to bring back that construct of the pairing of black studies and community studies in the broader sense. That more started in grad school.

Did you get the sense that this was rare to have such an established goal in mind so early on?

Stovall: I had mentors who would always make that pairing. One of them is a historian named James Anderson. He said the study of black life in the western hemisphere goes in so many different directions. People do literary analysis, historical analysis, psychological analysis, anthropological analysis, and those should all be under the broad umbrella of education broadly defined. But he always asked how do you make it make sense, and how is it palpable for the people that you care about? To me, from that space, combining what I was doing in community work with higher red, both groups of folks were asking that question ‘what does it mean to the folks that you care about?’ That was the larger struggle to articulate but one that I wanted to engage.

And now that you’ve done a lot of work in this, what do you think are the existing gaps in answering that question?

Stovall: One of the things is having education or colleges of education on that island that is not bridged back to black studies—it’s something that definitely needs to be addressed. Education at large as a social science needs to be addressed. Education at the level of community engagement needs to be addressed. The pairing of our understanding of the relationship between gender, race, and education need to be understood on a deeper level. The last one that comes to mind is the connection between race, place and school. Those things show up to me pretty readily.

Why immediately the relationship between gender, race and education?

Stovall: There is a group of folks who have looked at the role of black women in education—k-12 education—there is this departure that is not articulated as well as it can be. And you do have some studies that do a really good job with it. This particular group of black women, starting in the late 1860s all the way to the present, there’s always been groupings of these black women who have made a very intentional decision to be less concerned with the conventions of school and much more concerned about what education means for the uplift and humanity of black people. And that’s a very distinct pairing. You get these ethnographies of these particular women who were revolutionary in their practice in saying the schools are our least concern. You want to have shelter where you can engage in learning, but they were always asking ‘what is this for? To what end? For what purpose?’ And I think that work, we’re seeing some of it emerge in the new scholarship. That thing around really challenging how we think about traditional conceptions of school in opposed to education as something that is purposeful and useful and palpable.

A lot of what you’re talking about is this rooting in history. Is that a question that you always have to answer? Why are we teaching these stories from long ago?

Stovall: I think in addition to the relevance it is also how we communicate it. The example I always think of is if you teach slavery solely as the act of human degradation and you don’t include resistance, it quickly becomes irrelevant. If you don’t pair that with a current instance or a contemporary instance, it also becomes irrelevant. So now pedagogically instead of placing history on that island, what does it mean to say we all are historical beings? I actually got that from a high school principal. He said we all are historical beings, and we are connected to something. We can choose to ignore it or interrogate it. That is the preeminent question: what does it have to do with anything? If we can perpetually ask that and now find ways to address it, I think that deepens our learning, and I think it deepens our capacity to ask questions of it.

Part Three of Interview Heading link

There was this article in the Lenny newsletter on #FergusonSyllabus. She was talking about how at the root of it all that people are so scared to talk about it that when she started the school year a lot of people were telling instructors not to mention it in their classes, and she was just thinking that this was so not what we’re supposed to be doing right now.

Stovall: Right. This notion around education or student engagement as this safe thing. That’s the furthest from education. That’s more order and compliance. If you are intentional about engaging the present and this connection to the past you’re going to have to get into this territory that is not safe or sanguine. It’s just the reality of that particular engagement but you want to do that because if you don’t then school just becomes more irrelevant than it already is in most cases.

With this idea of engaging, it makes me think of social media. What do you think about the use of this in discussing different topics in African American studies?

Stovall: It’s useful for understanding the world in a certain way. On one end it can be deeply educational and on another end it can be deeply narcissistic. I want to be as intentional as I can about my engagement with the world and that’s one of the reasons why I don’t have any social media presence. I’m not so protective. I’ve seen pics of me on Instagram or Twitter or comments that I’ve made on Twitter, and I don’t mind. But for me directly engaging in all those different avenues is a bit much for me, and that’s solely a personal choice because I’ve seen some folks do some pretty amazing things on social media. You have to take the good with the deplorable and terrible. For me, again, trying to be as intentional as I can with engagement is what drives my choice.

When you mention narcissism, there are so many discussions about academia and ego. Even when we talk about publishing books, the hope is that there is that intention and motivation that have to do with community, education, students, etc., but there is often a struggle with the ego. Do you agree or disagree with that?

Stovall: For me, there are some layers to it. I’m not a tech person. I’m luddite status in so many ways but at the same time this thing to your point around understanding this, there are a lot of parallels around academia and entertainment in the way in which work is disseminated, the way in which people are popularized, the way that people are held in very high or low regard. They don’t blast each other as much, but now with the advent, immediacy of social media, you see folks blasting each other, this in-fighting, and you have to understand that, and you have to understand how that’s gendered, how that’s racialized, how that’s classed, how that is keyed into issues of ability or disability, age—all of this stuff plays in and when questions aren’t asked of it, then it’s allowed to fester and capitulate. It’s passive-aggressive behavior in academia. You very rarely hear folks discussing it in academia and it needs to be called out. It’s this genteel nature between colleagues. But if something is fucked up you can’t just let it ride. You have to ask yourself ‘what are we actually doing?” And that can be confrontational, but it’s not something to run from.

It seems to depend a lot on the department.

Stovall: Right.

Are there things that students bring up that surprise you or stir things up?

Stovall: Every now and then, yeah. People bring up how they understand things, how they’ve come to understand things, and their experience in knowing things. They discuss this epistemological experience, how we come to know something, and that’s always interesting, because it deeply informs my approach to things. There hasn’t been any kind of shocking things, but there are many things that make me think for sure in terms of jarring my own trajectory or jarring my own interests or simply thinking “that’s a damn good question.”

Would you immediately call yourself an educator first or a researcher first or do you not like to do either?

Stovall: I would like to break that dichotomy and call myself a struggling educator. If I had a website my byline would be “struggling educator” because there is one thing to know something, it’s another thing to do something because you know it, and there’s a third thing to even communicate what you know and what you’re doing because you know it. I think that’s the more accurate description.

Has it been easier since you first started teaching?

Stovall: [laughs] No. Some questions are very old, and then some are new, and others are more layered. I think in academia you can make a decision to stop wanting to learn if you so choose, but I think it takes us further away from the justice condition.

Part Four of Interview Heading link

A lot of people are afraid to learn. In that article I mentioned she said that one of her students said that when people do want to talk about things it’s only in the safety and comfort of a classroom or online and people don’t want to in “real life.” Where do you think this fear is coming from?

Stovall: In some places, especially in how you construct classrooms, school can be the place to engage these more difficult things—it can be, it’s not necessarily designed to be—but in life sometimes it’s just the fatigue to engage things. It’s like damn, we’re trying to eat and he’s talking about crazy shit. It’s like family gatherings—there used to be this thing where family members would say to me “here you go…” In life we’ve become so imbued with getting through the day to day and having some semblance of rest, and a lot of that is the travails of capitalism, but folks are heavily bound to that in terms of needing a place to live, something to eat, and some form of clothing. This thing around seeking out the basic needs and this struggle to have a peace of mind. Critical analysis very directly interrupts any sense of peace of mind, so now getting into self-care becomes much more of a challenge. I think a lot of times people are dealing with that in the day to day, and one of the places of refuge, if you will, if you call it that, can be a classroom. But it has to be a commitment of those in the classroom to do that. School in this traditional form is structured around order and compliance. You’re rewarded by order and compliance. This teacher was saying how are we need to be intentional about breaking that traditional trajectory, and what does that mean for our work?

She [Marcia Chatelain] did mention a lot of people emailed her asking how she would get around these direct orders to not discuss it, and I wish she had mentioned her advice. For classes that are not inherently rooted in any kind of civic nature, activism, engagement, how do you make those classes relevant to those things if there is that structure required of you?

Stovall: Content. You may have these guidelines, but I think the way to make an adjustment is to look at the content. What are you actually talking about? How can you unravel this thing by asking these important questions? It makes planning a class very different. I’m thinking about a colleague where he has a selection of readings and then the students go into the readings and collectively they decide the order of the readings for the semester. So it’s really interesting. It’s him modeling collective design. It’s this thing around really looking at that content. Anything can be made relevant. There just has to be intention around its relevance.

So we’ve been talking about structure to a classroom, but there are also many ways an academic as an individual structures a day. What is a normal day for you?

Stovall: There is no normal beginning and end. For me it’s trying to get some kind of meditation/exercise upon waking, then either meetings or readings or research, in the middle there’s teaching and then some ending ritual whether it be eating, sleeping, or catching a drink with somebody. Those are the things that are usually involved in the day. Scheduling that has always been a challenge for me. I’ve been a little bit better, but it gets a little funkier when it comes to travel. For me, it’s always October, November and March, April. Those two sets of months are horrific. There are conferences, talks, and workshops. Those months are funky.

Have you ever had a 9-5 job?

Stovall: No. I had food service/hospitality gigs and manual labor. When you said 9-5 I initially thought about the 9-5 space. I use to open a café everyday but it was 6-1. I finished undergrad, worked, and then came back to grad school. There are a lot of different directions you can go in. Some jobs can be more menial and some more meaningful to who you are as a person. I’ve just always had that hustle and survive, make-do mentality, before I got a position in academia. The philosopher and economist David Harvey is right in terms of the limits of capital. Our world is shaped around work and how we even configure it in when we use the term supporting oneself.

Well, we could keep talking about that one forever.

Stovall: [laughs] Yes, we could.